In 2015, researcher John Hattie updated his seminal research Visible Learning. Hailed as “teaching’s Holy Grail,”1 Hattie synthesized 15 years of research on more than 800 meta-analysis about what works in the classroom. His goal was to focus educators around the idea that all students should make at least a year’s worth of progress for a year’s input.

Hattie found that most of the classroom activities we engage in have some effect on student achievement and even memorably noted “perhaps all you need to enhance learning is a pulse!”2 but he was also able to determine the average effect of classroom practices.

Hattie argues that unless a factor provides more impact than the average teaching activity, it shouldn’t be used to make decisions about what happens in classrooms.

Effect Size in Education

For those of us who aren’t statisticians, effect size works like this: Imagine you’re taking a road trip from Boston to Chicago. If you drive an average of 60 MPH, you’ll spend about 17 hours covering those 1,000 miles. Now imagine you can drive as fast as you like; 85 MPH cuts the trip down to 12 hours. Double it to 120 MPH and you’re rolling into Chicago in about eight hours.

Teaching practices work the same way. Cooperative learning, providing enrichment and afterschool programs have an effect size around the average of 0.4 (average impact). Things like charter schools, student gender and teacher’s level of education are around 0.1 (almost no impact,) while feedback, acceleration and formative assessment are around 0.7 (better impact).

Hattie’s goal was for us to use his research to develop practices that drive improved instruction and results.

Best of the Best

The 2015 update to Hattie’s original research uncovered some interventions that eclipse every other classroom activity with their effect on student achievement.

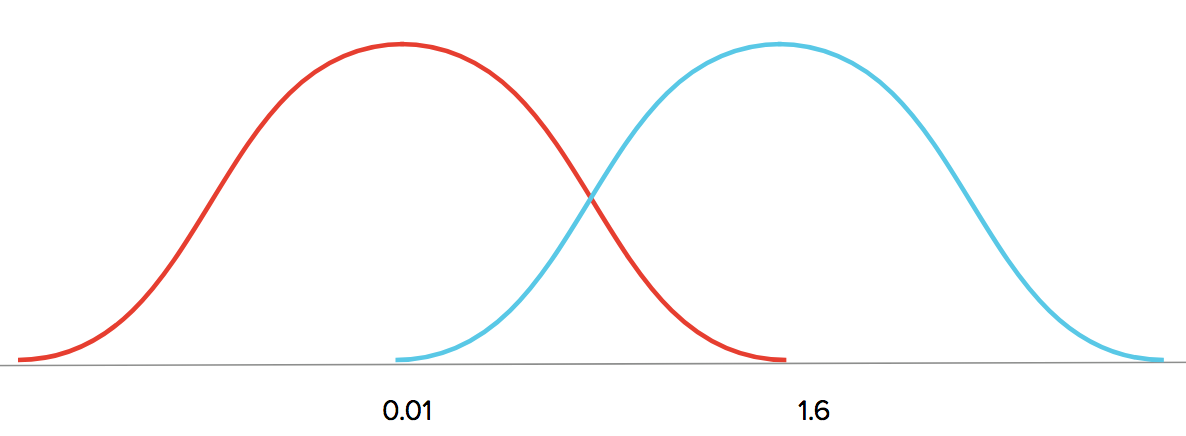

Conceptual change programs, self-reported grades and collective teacher efficacy all have effect sizes greater than 1.15. To put that into perspective, if you compared collective teacher efficacy at 1.57 to student control over learning at 0.01, 95 percent of your students in the “control” group would perform worse than the average student in the efficacy group.

That’s essentially changing the achievement distribution in your classroom from the red curve to the blue one below.

Given that these super effects have such a powerful impact on student achievement, they’re worth examining.

(Next page: The 4 ways to supersize Hattie effects)

1. Conceptual Change Programs

Conceptual change programs (1.16) are a newcomer on Hattie’s list. The idea is that a learner’s prior beliefs can be resistant to change, even when presented with new information.

For example, think about teaching a lesson on climate science. Students might initially believe that climate is persistent and human activity doesn’t affect it. After consuming information about climate change over time, students may recognize that some climate variability is due to the natural periods of warming and cooling the globe has undergone for millennia. The original mental model adapted to accommodate new information.

However, sometimes students don’t assimilate all the new data into their mental model. Often this is solved with re-teaching, but it would be more effective to change our focus by directly confronting common misconceptions. In this climate example, some common misconceptions could be that global warming is fake news since this winter was colder than last winter, or that it’s due to the sun or water vapor, or that CO2 has no real effect.

Specifically addressing these misconceptions will have a much greater impact on learning than simply re-teaching.

2. Self-Reported Grades

Self-reported grades (1.3) is another Hattie super effect, but isn’t new to the list. (Hattie noted that if he were to write Visible Learning again, he’d call this concept “student expectations.”)3

When a teacher knows what a student’s expectations are, they’re able to push the student to achieve more. Different than goal-setting, this practice of stretching student expectations grounds future goals and behavior changes in what a student believes about his or her ability to perform today.

3. Collective Teacher Efficacy

The highest changeable effect on Hattie’s list is collective teacher efficacy (1.6).

An intervention of this magnitude can essentially triple the typical rate of learning. That’s more than double the size of feedback (0.7) and five times the size of homework (0.3.)

Efficacy beliefs are this powerful because they influence teachers’ actions. Research shows that perceived efficacy directly changes “the diligence and resolve with which groups choose to pursue their goals.”4

When teachers believe their collective efforts can change student achievement, they’re right. When they believe there’s not much they can do to influence results, they’re still right and our behavior reflects it.

There are many factors that contribute to teacher efficacy including the degree to which teachers participate in decisions, how much they know about what peers are doing and how responsive school leadership is.

However, according to Hattie, there’s nothing better that can be done to influence student achievement than teachers believing their teaching directly benefits their students.5

4. Being Willing to Make Changes

Here at Canvas, and in education in general, we’re always looking for ways to help students learn more, achieve more, and make progress faster. That’s why we hunt for evidence-based ways to move the needle. But just like our students, in education we sometimes hold on to unhelpful beliefs in the face of contradictory evidence.

There’s nothing unusual about our resistance to change—it’s human nature. However, as educators, we can and should take time for introspection, leveling-up our expectations for ourselves and recognizing areas of improvement.

Armed with Hattie’s data about what works, maybe a little good technology and a supportive professional community, we have the power to increase our own self-efficacy and the ability to deliver super-sized results for all our students.

- https://www.tes.com/news/tes-archive/tes-publication/research-reveals-teachings-holy-grail

- https://visible-learning.org/

- https://visible-learning.org/glossary/

- Goddard, R., Hoy, W., & Hoy, A. W. (2004). Collective efficacy beliefs: Theoretical developments, empirical evidence, and future directions. Educational Researcher, 33(3), 3-13.

- Donohoo, J. (2017). Collective efficacy: How educators’ beliefs impact student learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- 7 reasons to ditch recipe-style science labs - November 22, 2024

- As a paradeducator, here’s how I use tech to help neurodivergent students gain agency - November 22, 2024

- 5 ways school districts can create successful community partnerships - November 21, 2024