North Carolina’s brand new Digital Learning Plan is generating buzz in schools and at the capitol. Here’s what other states can learn

Like every state, educators in North Carolina are struggling with complex demands around digital learning.

Like every state, educators in North Carolina are struggling with complex demands around digital learning.

In the era of personalized learning-meets-BYOD, and with a big push on 21st century skills, districts and education leaders can still feel pretty isolated as they work out where to go next. And conveying their needs to state legislators, who often have the power to regulate funding and set the pace for any statewide digital initiatives, can be yet another challenge.

“A lot of people tell us that these kinds of digital initiatives get written at the Capitol, when the focus should be on engaging stakeholders at every level,” said Jenifer Corn, the director of evaluation programs at the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation.

When the state’s department of education decided to educate lawmakers, district leaders, and other stakeholders and set North Carolina’s digital learning future, they turned to Corn’s organization to do it in a systematic, data-driven way that gave a voice to nearly every educator in the state.

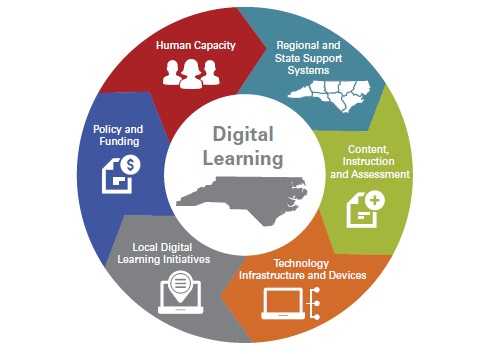

Recently, the Friday Institute released the results of that 18-month-long effort, the North Carolina Digital Learning Plan, which outlines both recommendations and specific goals for education leaders and policymakers around digital-learning related topics, such as infrastructure and devices, professional development, instruction and assessment, and funding.

The DLP is, in part, a response to two new state laws passed in the last legislative session — that schools must transition to digital resources by 2017 and that colleges of education, teachers, and administrators would be responsible for meeting new digital competencies. The state’s department of education contracted with the Friday Institute on how to implement those goals simultaneously.

In response to that charge, the Friday Institute, a policy and research land-grant which is part of the college of education at North Carolina State University, began by checking in with districts one by one. They criss-crossed the state conducting needs assessments and asset management surveys. They spoke with all 115 local education agencies and held town hall meetings. And, during that process, they collected a lot of data.

“This was the first time every bit of the institute was touched by the same work,” Corn explained. “We were building buy in so [everyone] really felt like this wasn’t the Friday Institute telling people what to do, but it was reflecting back to the folks in Raleigh about what was happening.”

A digital snapshot

In addition to those deep dives, the institute also developed an ed-tech rubric and assessed every district’s digital progress. “For the first time,” Corn said, “we have a snapshot of where every district in the state falls along a continuum about where they thought they were in terms of readiness in technology.”

As might be expected, few districts are in truly advanced stages of their digital transitions. According to results from the rubric, about 19 percent of districts in the state confessed to only just beginning to move toward digital, while just six percent rated themselves advanced. The vast majority said they were in a developing stage.

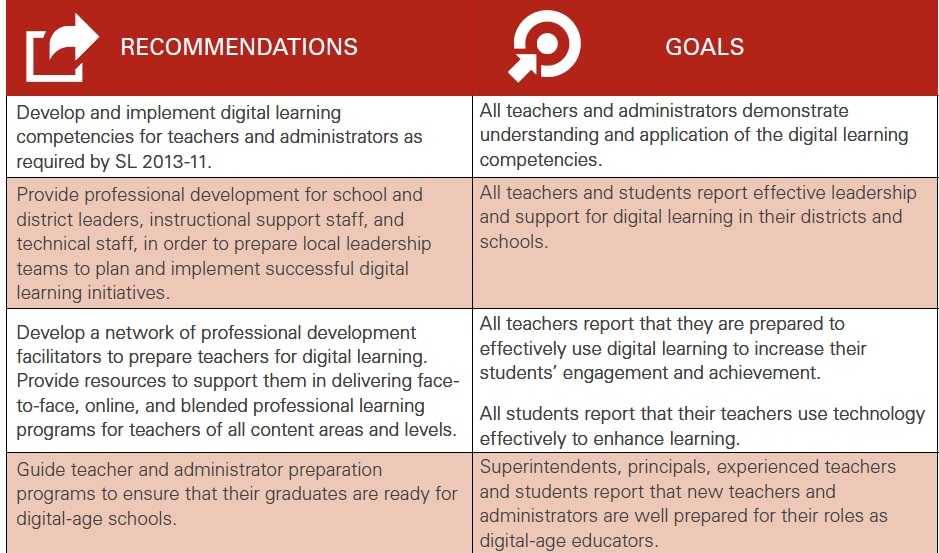

For them, the DLP might serve as something of a roadmap, or at least a set of goals to aspire to. While many of the recommendations can be read as a call to action for statewide organizations and leaders, specific goals — spelling out the skills and resources teachers, administrators, and schools should possess as they enter more advanced stages of their digital transitions — can help school and district leaders at every level in their planning.

An example of the recommendations and goals from the Human Capacity section. Click image for full size.

Of interest to both lawmakers and educators, the DLP makes recommendations around providing flexible professional development for district-level staff and principals, as well as the creation of a larger network of PD facilitators devoted to helping teachers adjust to digital learning concepts, such as blended instruction. It also suggests beefing up regional and statewide collaborations to support local educators and developing sustainable funding models. Of course, many of these initiatives will require new funding, and the report takes pains to spell out where federal money can step in and what, exactly, the state might be on the hook for.

“It’s been quite a budgetary fight,” Corn said about working with legislators to secure those funds. “But we did get an increase in textbook allotment and school connectivity. We didn’t get everything we asked for but because of the Digital Learning Plan and the conversations we’ve been having, at a time when our state budgets have been fiscally conservative, they did give increases in those two areas.”

Right now, Corn and her team are talking up the DLP to legislators and continuing their work. A toolkit for district tech directors is in the works and they are in the early stages of considering a data clearinghouse that education leaders can use to more easily find out what kinds of technology their colleagues across the state are buying — and using.

The overall goal of the DLP, she said, was to make it easier for everyone to come to grips with a digital world, no matter what their role in education. “The model that we developed, it could certainly be applied to other states,” Corn said. “This is about changing the role of the teacher in the classroom, changing the way school works. It’s not about the devices or the technology.”

- TC- What student choice and agency actually looks like - November 15, 2016

- What student choice and agency actually looks like - November 14, 2016

- App of the Week: Science sensor meets your smartphone - November 14, 2016